|

Mountains and Rivers

By Friedrich Dimmling

Even as a child, printmaking fascinated Eva Pietzcker, the almost

magical emergence of an image as the paper is pulled from the block. Clearly,

it has been a long journey leading to her current masterpieces of Japanese woodblock

prints, images which, with their intense calm power, prompt a comparison to

those of such artists as 趙孟頫 Zhao Mengfu of the Yuan dynasty. What has been

said about his contemporary, the Daoist 方從義 Fang Congyi, applies just as well

to Eva Pietzcker’s work: “He painted landscapes which gave form to the formless

and which transformed the formed into an existence beyond form.” ›Mountains and Rivers‹, 山川 shan chuan, is the

Chinese Term for landscape. As mountains and rivers—or their absence—form a landscape’s

character, so the rocks and water levels in Eva Pietzcker’s prints give hints to the

magical presence of the captured sceneries.

Eva Pietzcker, who was born in Tübingen in 1966, studied Fine

Art at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Nürnberg from 1987 until 1992, and

then at the Hochschule der Künste in Berlin. Since 1991 she has worked as a

free-lance artist in Berlin with a focus on printmaking, initially working on

etchings and screen prints. With her discovery of the Japanese style of woodblock

printmaking she found her true medium. About this technique she writes: ”Compared

to the Western method, where oil-based ink, applied to the block with a roller,

is printed onto the paper's surface with the help of a press, in the Japanese

style, watercolor paint is applied to the block with brushes and printed by

hand allowing the color to seep deep into the soft Japanese paper. As a result,

these Japanese style prints tend to have a more painterly appearance and can

often resemble watercolor paintings.”

This technique lends itself well to the art of landscape painting,

which quickly became the major theme of Eva Pietzcker's work. From her images, qualities of deep stillness and intense expression emerge. The creation of these

prints happens in two stages. On location, often after hours of searching for

the perfect view, sometimes sitting in a small boat on a lake, a water-color

drawing is created by quick sketching. Sometimes it is like a race with the

light, as it changes from one moment to the next. Afterwards, at home in the

studio, the plates are cut requiring high precision and quiet concentration

in an atmosphere of meditative focus. The communion of these two poles: the

lightning-fast sketching of a fleeting mood without room for calculating thoughts,

and then the process of translation through the cutting of the blocks with absolute

concentration and free from distraction - these are the outer processes by

which these works of mysterious and fascinating effect are created.

I first came to know Eva Pietzcker's work in a small gallery

in Berlin Kreuzberg. More specifically, it was on an invitation card for the

opening which featured an etching by Eva Pietzcker, chosen by the gallery owner

with the assumption that it's overwhelming impression would attract visitors

to the gallery. It was a true “Oh wow!” experience. The card accomplished its

mission. I visited the show – and I purchased the print.

Now if I ponder the question, what is it that so fascinates the viewer about Eva's prints, that literally pulls the viewer in, I find myself in some tricky

territory. For experts it is easy to talk about art, so long as they assess

the technique, classify the style, or explain the artist’s contribution to the

genre. Certainly technical mastery contributes to the impact of the work, showing

itself in the complex multi-color woodblock prints with their hairline contours,

impressive even to the layperson. Yet the impact on the viewer is no less strong

in the works which appear, on the surface, to be more simple. Moreover, modern

day observers have so come to expect perfection in art that they would rather

comment on its absence than appreciate its presence. The impact of Eva’s work

on the viewer has perhaps more to do with that transcendent dimension which

distinguishes true works of art from those which only strive to be. To say something

of substance about this is difficult for a person of these rationally-oriented

times. A woodblock print is an image, whereas our modern language – with the

exception of poetry of course – is more specifically suited, through the use

of well-defined terms, for depicting objective connections. So for this question

a poem may be helpful, perhaps one of the legendary poems from the Tang period,

famous for their natural ambiance.

白日依山盡,

黃河入海流。

欲窮千里目,

更上一層樓。

On the tower

A radiant sun sinks slowly behind the distant mountains.

There, the yellow river that pours out into the sea.

Do you wish to see further still?

Then climb up to the next level.

Eva has long put the spirit of this poem's conclusion, which

has become a common expression in Chinese, into action with both passion and

curiosity: studies of Japanese woodblock printmaking in Japan and research of

the traditional Chinese methods both in 2003; studies into Japanese paper-making

in 2004; working with porcelain in China in 2009; and several work stays in

the USA and Canada. Eva Pietzcker constantly strives for a more complete understanding.

Without the remarkable level of dedication and deep exploration that she shows,

perfection within this challenging technique could hardly be achieved.

To explore the mystery of the transcendental dimension mentioned

above, I want to approach this theme from the Asian side. The main advantage

of this approach is that the ominous term of transcendence, so easy to define

yet so difficult to comprehend, becomes less intimidating because it is non-representational.

Our understanding of transcendence, as something that lies a priori beyond the

possibility of sensual experience, exists only in Western culture. The rest

of the world, especially Asia, knows only one world. The cosmos as it is understood

in Chinese culture, and here I refer to the cultural region broadly, is a world

of appearances. This is most clear in the Chinese language itself where the

written language is image. And it was not without reason that the Japanese language

did not abandon the use of Chinese characters.

This approach, the rejection of clearly defined terms in favor

of a pictorial script, as the starting point for an intellectual understanding

of a subject, however, has its price. We end up with terms, which have become

popular in the West, such as 道 Dao, the Way, which stands for the primordial

nature of a thing or a person. Or we come upon statements such as 大象无形 “The

perfect image has no form”, which we feel we can almost understand, but which

then, because of their elusiveness, leave us perplexed in the end. To avoid

being accused of esoteric ramblings, I should note here that Chinese terms always

appeal to the reader's own horizon of experience. The reader, based on her own

experience or literary knowledge, must already have or must develop her own

understanding of the characters. The pictorial script lacks the objectivity

of our terms, which are advantageous for interpersonal communication, but in

return it opens a pathway into worlds which remain inaccessible in the case

of objectivity.

It is the greater directness of this approach which enables

written characters to successfully convey meanings, just as it enables images

to have their intense emotional impact on a viewer. This jaunt into the particularities

of Asian and especially Chinese culture can be justified because of the clear

echoes in Eva Pietzcker's woodblock prints of the Asian world and because of

the artist’s deep interest in Chinese and Japanese culture, and especially in

its Arts. It is not only the technique itself, the Japanese way of woodblock

printmaking, but also the main theme of her work, nature, including its sometimes

less spectacular aspects which still leave a deep impression on the human soul,

and whose essence she inimitably captures in her work.

To follow this essential idea still further, I want to incorporate

the approach sketched above and rely upon the image language of the Yi Jing

(I Ching). This ancient Chinese work known as the “Book of Changes”, interprets

the world of phenomena through 64 images. Each image is composed of two out

of eight possible trigrams. The term trigram refers to their make-up of three

lines, each either continuous or interrupted, which represent the yang or yin

character depending upon their relative positions. Some trigrams evoke images

of nature which in turn lead to related insights. It is these trigram symbols

that may now be helpful in bringing the essence of an image closer to the realm

of conceptual understanding.

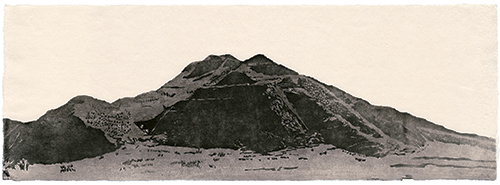

The Standstill, the Mountain

The Standstill, the Mountain

The Yang line has come to the end of its ascendancy and arrives

there at its standstill. An unfolding, a creating force, has come to its completion,

has taken, at least temporarily, its ultimate form.

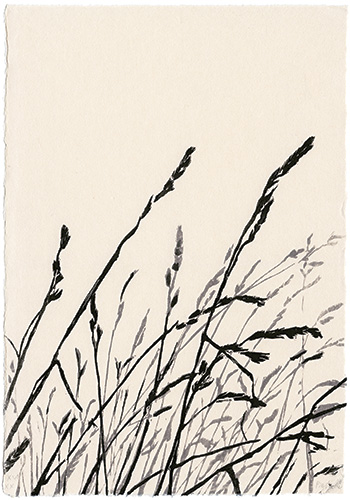

The Gentle Penetration, the Wind

The Gentle Penetration, the Wind

A Yin Line pushes up from below into a purely Yang constellation.

The Soft takes hold of the Solid and transforms it. A gentle breeze brings grain

stalks into movement, transforming the seemingly lifeless and still grasses

into an undulating ocean.

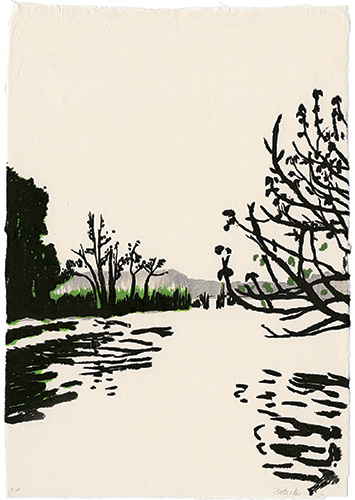

The Joyous, the Lake

The Joyous, the Lake

Benignly radiant, the lake's surface lies before the viewer,

a peaceful and joyous image. The Soft, the Yin, is on the surface and defines

the image, which otherwise consists of only solid Yang lines. In contrast to

the first example, the Mountain, here the supple water, which cannot take a

solid form, shapes the surface rather than the hard rocks with their bizarre

forms.

Perhaps this exploration of Eva Pietzcker's block prints through

the lens of the Book of Changes has brought you further into her images, possibly

even left you, in some small way, changed by them. The Chinese term for the study

of a painting, 读画 du hua, when translated literally, means “to read the image”. In this

sense I wish the observer a fascinating, joyous, and horizon-expanding reading

of her work.

Berlin, February 2013

|

|