Intaglio

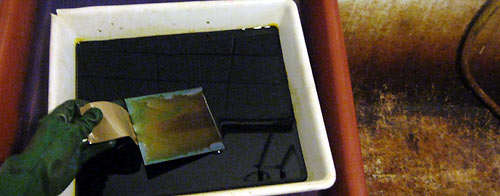

In intaglio printmaking, depressions are scratched,

cut or etched into a flat metal plate. When the plate is inked and wiped, the

ink remains only in the depressions. Printing the plate onto a humid paper with

a press creates a side-inverted image.

Printmaking techniques basing on the same principle are engraving and mezzotint

(see below).

History

The development of intaglio printmaking is connected to the

beginning paper production in Europe in 1390 and the work of goldsmiths

and armourers. Cutting and engraving metal was common for a long time as well

as inking these engraved depressions for decoration. From recording designs

by rubbing engraved motifs with or without inking onto paper it was only a short

step to using this technique as a way of artistic reproduction.

The first copper engravings were done probably around 1430.

In engraving, fine lines are cut into a brass or copper plate with burins from

steel. Intaglio developed some decades after woodblock printing, resulting from

the fact that it was more complicated than woodblock printing, which in addition

followed the pre-stage of cutting seals which had already been known for some

time. Compared to the popular woodblock prints, intaglio prints found their

audience rather among aristocrats or wealthy citizens, probably resulting from

the higher refinement in technique and visual impression. Intaglio prints were

also in demand as this way art works could be collected at reasonable prices.

Compared to woodblock prints, the images shown in the intaglio print were far

more secular.

Engraving developed first in the South-Western

part of Germany and in Switzerland. Though

there were influences on Asian printmaking, intaglio is rather a European

printmaking technique. Drawing was part of the goldsmiths training, and thus

the first engravers were goldsmiths, today no longer known by name. First outstanding

engravers were the "Master of the playing cards" and the "Master

E. S." among others.

For a while the technique was practised mainly by artists

as Martin Schongauer from Germany and Hendrik Goltzius and Lucas van Leyden

from the Netherlands. The engravings of this time were showing both religious

and mundane images. While the German artists leaned stylistically closer on

the middle age at a higher technical standard, the Italian Renaissance artists

as Andrea Mantegna and Maso Finiguerra created prints which appeared more "free".

In the second half of the 15th century, the technique of drypoint

emerged. Lines were scratched into the plate directly with a sharp needle, thus

creating a burr on both sides of the line. A first artist using this technique

was the "Master of the house book", who was working in Germany between

1465 and 1500. As the emerging burr was compressed again after some printings

and only a few copies could be pulled, drypoint was often practised by artists

for re-working already cut or etched plates.

As in woodblock printing, Albrecht Dürer

(1471-1528) from Nürnberg was an artist of highest significance also in

engraving. From travelling in Italy familiar with the Italian Renaissance engravings,

he created prints which brought this technique to a completely new level of

art.

Temporarily, he also worked in the new technique line

etching, emerging in the end of the 15th century. Lines were now not

cut or scratched into the plate, but drawn into a wax layer on the plate and

later etched in an acid bath. This made drawing much more easy and spontaneous.

First artist who were working with line etching were Urs Graf from Switzerland

and Daniel Hopfer from Augsburg, Germany. Line etching was also combined with

engraving. In the 17th and 18th century, line etching was used by painters and

drawers as Rembrandt und Claude Lorrain or later Tiepolo and Piranesi.

Engraving however was practised since the mid

17th century predominantly by professional engravers. These

were mainly ordered by publishers or artists to copy already existing images.

Engraving was used for reproducing paintings, for book illustrations or producing

maps.

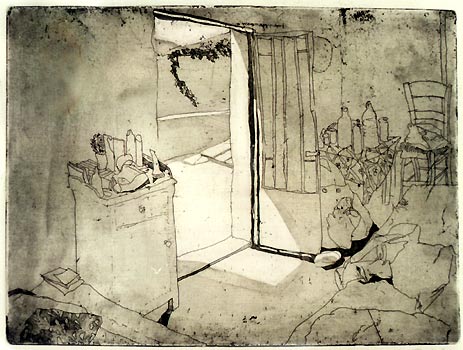

Fig.: line etching with aquatint, 1990

In the mid 17th century also a technique called aquatint

developed. It allowed creating even areas of different tones. However it was

common only in the 18th century. A master of aquatint was Francisco Goya, who

as the Spanish court painter expressed the societies dark side in his "Caprichos".

With the rise of wood engraving in the 19th century and the

invention of lithography and photography, copper engraving became less important.

Since the mid 19th century, a change in the evaluation of prints

took place and the term of "original print" was born.

Printmaking artists confederated in associations. Mostly these were painters,

who also made prints, creating their plates by themselves and sometimes even

printing them, treating the processes rather creatively. For the first time,

prints were signed. At first, artists mainly preferred to create intaglios and

lithographs, often in form of book or portfolios on order by publishers. Artist

creating these new "original prints" were in France artists of the

"Barbizon School" and some of the Impressionists, in Germany Impressionists

as Liebermann or Slevogt, also Käthe Kollwitz und later the Expressionists

with Beckmann, the "Brücke" artists and many artists who were

published by the committed art dealer and publisher Paul Cassirer in Berlin.

He also contributed to a new prime of printmaking in Germany by publishing in

1909 Hermann Strucks book "Die Kunst des Radierens" (The Art of Intaglio),

which made the technique available to a bigger audience.

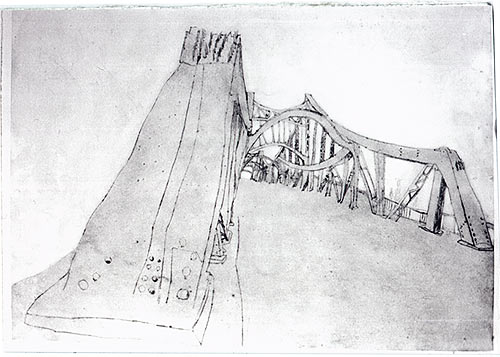

Fig.: drypoint, 100 x 70 cm, 1992

Technique

Engraving

Fine lines are cut with steel burins from various profiles

into a plate from copper or from brass, which was mainly used in the early years.

The burr which emerges on both sides of the cut line is later removed with a

scraper.

Drypoint

Drypoint is the easiest and most direct technique in intaglio.

With a sharp needle from steel lines are scratched directly into the plate,

thus creating a depression with burrs on both sides. When being inked, the ink

remains not only in the depression but also around the burrs. The printed line

has a special soft and velvety appearance. As the burrs are compressed during

printing, only small editions can be printed.

Line etching or hard ground

The plate is covered with a thin layer of wax or varnish which

hardens after drying. By drawing lines with an etching needle the covering layer

is removed. During etching in an acid bath the opened areas are eaten by the

acid and this way become deeper. The lines thickness and deepness depends on

the duration of etching, the chosen acid and the used ground.

Vernis Mou or soft ground

The plate is covered with a thin layer of a special wax which

doesn't dry but keeps soft. A thin paper is put onto the laminated plate which

can be drawn on with various drawing tools like pencil, crayon or a brush handle.

Also objects like leafs can be pressed into the soft ground. During drawing

the wax sticks to the paper and the plate's metal surface is uncovered. In the

acid bath, these areas are deepened. This technique reproduces the special qualities

of the used drawing tools perfectly.

Aquatint

For etching grey tones, a kind of raster is applied to the plate

in form of many small acid-resistant grains. In traditional intaglio this is

done by melting fine resin or asphalt dust grains onto the plate. Today, also

acrylic can be used by spraying it onto the plate.

In the acid bath, the acid bites between these small grains. The longer the

plate is being etched, the deeper the depressions between the grains will be,

thus holding more ink when being inked and displaying a darker tone when the

plate is finally printed. To produce tones, parts of the plate are covered with

acid-resistant varnish during etching steps.

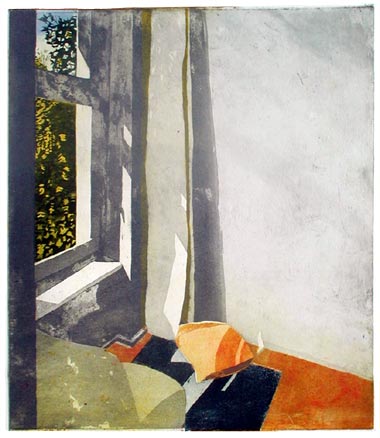

Fig.: Aquatint (three plates with four colours), 2003

Open bite

When open areas of the plate are being etched in acid without

an aquatint grain, in these areas the plate becomes just thinner. During inking,

the ink remains only in the edges of these areas. So areas etched without aquatint

show just lines in the final print.

Mezzotint

In mezzotint, the process is rather negative, working

from dark to light. The first working step is roughening the plate's surface

evenly with a rocking tool. After that, parts of the plate are polished with

a scraper, this way levelling the plate's depressions.

Bibliography

Brown, Kathan: "ink, paper, metal, wood", Chronicle

Books, San Francisco, 1996

Mayer, Rudolf: "Gedruckte Kunst", VEB Verlag der Kunst,

Dresdnen, 1984

Sotriffer, Kristian: "Die Druckgraphik – Entwicklung,

Technik, Eigenart", Schroll & Co, Wien, 1966

Saff, Donald and Sacilotto, Deli: "Printmaking: History

and Process", Wadsworth Inc Fulfillment, New York, 1978

Wye, Deborah: "Artists & Prints – Masterworks

from the Museum of Modern Art", The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2004

|